From Fossil Fuel Vulnerability to Clean Tech Dominance: China's Five-Year Plan and the New Geopolitical Battleground

- Jan 28

- 8 min read

October 2025, China published its 15th Five-Year Plan focused on "new quality productive forces." Three months later, U.S. forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. On the surface, these events appear unrelated. In reality, the Venezuela crisis is precisely the kind of geopolitical shock the Plan was designed to counter, consolidating the strategy's urgency and direction.

Introduction: The Strategic Imperative of China’s 2026-2030 Five-Year Plan

China’s forthcoming 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-2030) represents a critical blueprint for national development, centered on the concept of "new quality productive forces" to achieve technological self-reliance and innovation-driven industrial modernization1). Its formulation is a direct response to three converging pressures: The need to sustain economic growth amidst global headwinds, intense technological competition with rival powers, and the escalating imperative of climate action.

The main goal reveals a profound underlying strategic importance. Beyond that, the Plan is fundamentally structured to systematically address a core national vulnerability: fossil fuel dependency. By orchestrating a state-driven transition to clean energy dominance, it aims not only to meet environmental targets but to secure China’s economic resilience and reposition it as the indispensable leader of the next industrial revolution.

Analysis: Fossil Fuel Dependency as a Core Strategic Weakness

A primary analytical focus of the 2026-2030 Plan is its pronounced emphasis on developing "new quality productive forces" in clean energy. While this explicitly supports China’s climate goals, it also delivers a clear strategic message: China intends to systematically reduce its dependency on imported fossil fuels. This pivot is driven by a critical vulnerability rooted in its economic structure.

China, as the world's largest manufacturing nation accounting for approximately 29% of global output2), has an economic trajectory inextricably linked to its energy security. The global energy market upon which it depends is defined by three indispensable pillars—crude oil, coal, and natural gas (primarily traded as LNG)—which together constitute approximately 80% of the world's total primary energy supply3). Within this system, China occupies a position of profound import dependency as the world’s largest importer of both crude oil and LNG4)5), while also being the largest producer and consumer of coal6). This reliance is not merely a matter of supply but a foundational strategic weakness.

Economic Exposure: Heavy reliance on imported fuels exposes China’s economy to global price volatility. As oil accounts for approximately 3% of global GDP7), price spikes translate directly into higher costs, inflation, and pressure on trade balances, acting as a brake on stable growth.

Geopolitical Passivity: Dependency diminishes negotiation power and creates vulnerability to supply chain disruptions rooted in geopolitical tensions. This risk was starkly demonstrated in early 2026 when U.S. forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro—a key oil exporter deepening ties with China—during a large-scale military operation in Caracas8). This unprecedented enforcement action, leading to his indictment on narcoterrorism charges, directly threatened a critical energy supply route and challenged ongoing efforts toward non-USD settlements. For China, reliance on sea-borne energy from regions subject to such adversarial interventions represents a critical and tangible national security risk.

The Developmental Trap: Turning to domestic coal for security makes China the world’s largest CO₂ emitter9), creating a tension between immediate industrial needs and long-term environmental goals. Furthermore, the high cost of import LNG, which is nearly three times the price of domestic coal10), alongside a technological gap in its infrastructure, limits swift diversification.

The detailed analysis of this fossil fuel situation underscores why China remains in a fundamentally vulnerable position. The Plan’s explicit clean energy focus is therefore not merely an environmental directive but a calculated strategy to mitigate this core economic and strategic weakness.

The Strategic Response: Detailing the Five-Year Plan’s Clean Energy Architecture

The 2026-2030 Plan operationalizes this pivot through a comprehensive industrial and policy framework designed to build clean tech dominance.

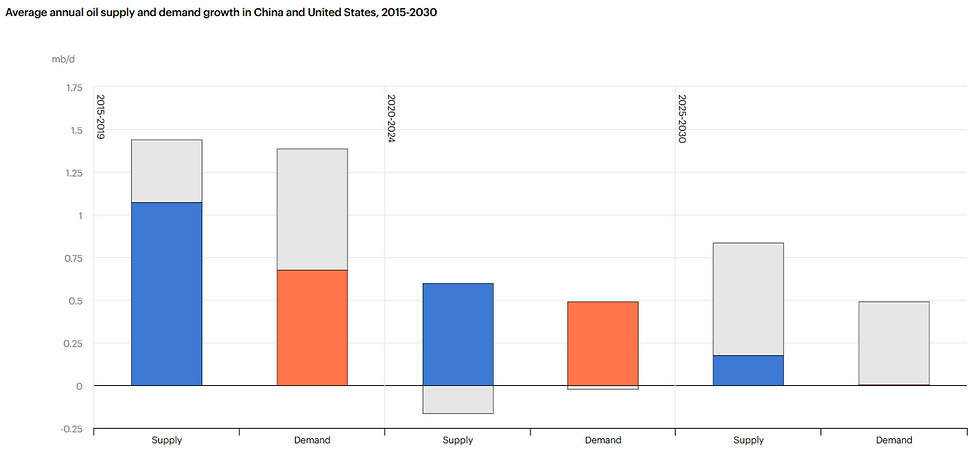

Dominating the EV and Battery Ecosystem: The electrification of transport is the centrepiece of this strategy. China's aggressive push is already altering global oil demand. The International Energy Agency (IEA) notes that China's oil demand is on track to peak this decade, driven by an "extraordinary surge in EV sales," the expansion of its high-speed rail network, and a growing fleet of LNG-powered trucks11). The IEA forecasts that global electrification will displace 5.4 million barrels per day of oil demand by 203011). By controlling the entire EV and battery supply chain—from lithium refining to cell manufacturing and final assembly—China aims to simultaneously cut its crude oil imports and establish an unassailable competitive advantage in a defining future industry.

Leading Renewable Energy Manufacturing and Deployment: Beyond vehicles, China is consolidating its position as the world's clean energy factory. It leads global production and installation of solar panels, wind turbines, and associated critical components. This manufacturing hegemony allows China to export its energy transition model globally, particularly through the Belt and Road Initiative, where it builds energy infrastructure and fosters cooperation with partner nations12).

Policy Targets Driving the Transition: This industrial shift is underpinned by clear national policy targets: peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. The focus is on creating "new quality productive forces" through green manufacturing, a circular economy, and the integration of digitalization with industrial processes. This transition is not about abandoning traditional industries but upgrading them through technological innovation to be more efficient and less carbon-intensive.

Future Outlook: Opportunities and Uncertainties

Opportunities

China’s strategic pivot offers significant potential benefits. Success would fundamentally enhance its energy security by reducing its exposure to volatile fossil fuel markets and vulnerable supply routes. Domestically, it positions China to create world-leading export industries in EVs, batteries, and renewable equipment, leveraging formidable cost advantages and vertical integration. This industrial dominance not only supports economic growth but also addresses severe domestic pollution, fulfilling critical ESG objectives.

Globally, leadership in the clean energy transition allows China to accrue substantial diplomatic soft power. Crucially, this is amplified through the Belt and Road Initiative, where China exports its energy transition model by building clean energy infrastructure and fostering cooperation with partner nations. This strategy simultaneously expands its geopolitical influence and promotes the international use of the RMB, signaling a shift in global currency dynamics.

Uncertainties – Geopolitical competition

However, this trajectory is fraught with inherent threats and challenges. The nature of this reconfigured competition is already visible in ongoing disputes, such as the U.S.-Venezuela conflict, which reveals multiple layers of strategic rivalry. A stark warning comes from the recent U.S.-Venezuela conflict, which highlights the persistent geopolitical friction between the U.S. and China. China’s BRI aims to break trade barriers and indirectly encourages transactions in RMB rather than USD, challenging the global financial system. This shift threatens the petrodollar system, which underpins U.S. financial dominance. When the U.S. intercepted Venezuelan oil shipments, one of the seized tankers was en route to China13), suspicion arose that oil was the real motive. Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven reserves—303 billion barrels (around one-fifth of global supply)14)—but its production is limited to 1.1 million barrels per day15). China is Venezuela’s largest customer, taking 55–80% of its exports, about 700,000 barrels per day, though this accounts for only 4.5% of China’s total imports16). The first layer of significance is clear: these transactions were conducted in RMB with discount price, directly challenging the petrodollar and signaling to other nations the risks of bypassing dollar-based trade.

The deeper layer is more strategic. Venezuela produces heavy crude oil17), unlike the light crude common in U.S. production. Heavy crude requires higher upfront investment for extraction and refining, but it is a superior feedstock for asphalt production18). China has invested over USD2.1 billion in Venezuela’s oil sector and an additional USD1 billion through private firms to develop heavy crude fields19)20). Asphalt is fundamental for infrastructure projects such as highways and airport runways, which are core components of Belt and Road development21). In China, asphalt already covers over 90% of expressway surfaces, underscoring its strategic importance22). Heavy crude’s link to asphalt means U.S. actions go beyond short-term oil interests; they aim to undermine China’s infrastructure ambitions under BRI, disrupt RMB-based trade, and reinforce the petrodollar’s global position.

This case demonstrates that while China’s five-year plan shifts focus to clean energy and "new quality productive forces," it effectively switches, rather than eliminates, the arena of great-power competition. The transition does not end geopolitical rivalry but merely shifts the battleground. The contest now expands to securing the critical raw materials—such as lithium for batteries, cobalt for EV motors, copper for electrical grids, and rare earths for wind turbines23)—that are the essential building blocks of the clean energy economy itself. China must now secure these complex new supply chains against concerted rival efforts to diversify sources and onshore processing.

Conclusion

In conclusion, China’s 2026-2030 Five-Year Plan is a strategic document defined by its response to vulnerability. The analysis reveals that its clean energy drive is fundamentally motivated by the need to overcome the economic exposure, geopolitical passivity, and developmental constraints imposed by fossil fuel dependency. The recent Venezuela-U.S. conflict underscores this logic: when geopolitical battles erupt over hydrocarbon resources, China remains in a strategically vulnerable position. The Plan’s primary aim is therefore to strategically develop dominance in clean technology rather than remain exposed in the old domain.

However, as the analysis demonstrates, this pivot does not escape great-power rivalry; it reconfigures it. China’s strategy foresees the inevitability of continuous geopolitical competition. By emphasizing clean energy, it seeks to avoid the entrenched vulnerabilities of the fossil fuel arena, but in doing so, it merely shifts the battleground to critical minerals, green technology standards, and the future architecture of the global energy trade. The Venezuela case, which remains unresolved, exemplifies the persistent tension that will inevitably resurface in these new theaters. The success of China’s strategic pivot will depend not only on its technological and industrial execution but also on its ability to navigate a reconfigured yet inescapable landscape of geopolitical rivalry. The outcome will determine not only China’s own economic and environmental future but also the balance of power in the coming era of green technology.

References:

Key things to know about formulation of recommendations for China's 15th five-year plan

Chart: China Is the World's Manufacturing Superpower | Statista

China could greatly reduce its reliance on coal. It probably will not

China imported record amounts of crude oil in 2023 - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)

World LNG Report 2025: LNG trade continues to grow,... | 2025/06/05

Oil revenue by country, around the world | TheGlobalEconomy.com

Nicolás Maduro captured by US forces and flown out of Venezuela

Biggest emitter, record renewables: China's climate scorecard

Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – Green Finance & Development Center

China’s Oil Investments in Venezuela - Energy News, Top Headlines, Commentaries, Features & Events - EnergyNow.com

Everything there is to know about Venezuela's oil (and why US companies are ready for it)

Private Chinese Firm Invests $1 Billion to Pump 60,000 Bpd Crude in Venezuela | OilPrice.com

Who Really Owns Venezuela's Oil? China vs. Trump Showdown Begins - Modern Diplomacy

Sustainable Asphalt Construction in China: Challenges and Innovations

The Dependency on Critical Raw Materials for Clean Technologies

Comments